2011-07-28

Minority Rules: Why 10 Percent is All You Need

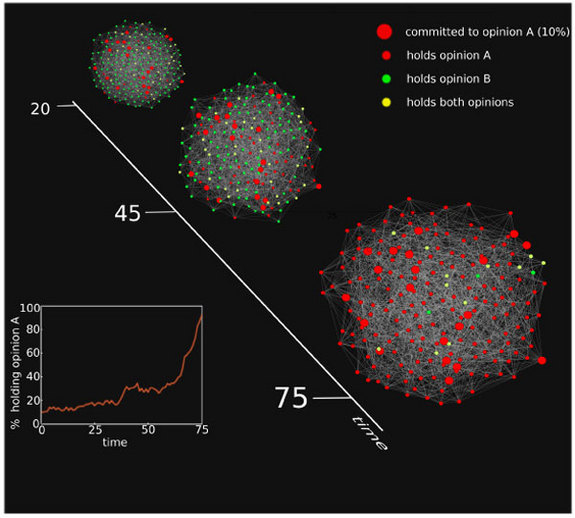

What does it take for an idea to spread from one to many? For a minority opinion to become the majority belief? According to a new study by scientists at the Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, the answer is 10%. Once 10% of a population is committed to an idea, it’s inevitable that it will eventually become the prevailing opinion of the entire group. The key is to remain committed.

The research was done by scientists at RPI’s Social Cognitive Networks Academic Research Center (SCNARC), and published in the journal Physical Review E. Here’s the abstract:

We show how the prevailing majority opinion in a population can be rapidly reversed by a small fraction p of randomly distributed committed agents who consistently proselytize the opposing opinion and are immune to influence. Specifically, we show that when the committed fraction grows beyond a critical value pc=10%, there is a dramatic decrease in the time Tc taken for the entire population to adopt the committed opinion. In particular, for complete graphs we show that when p

From a press release on SNARC’s website:

“When the number of committed opinion holders is below 10 percent, there is no visible progress in the spread of ideas. It would literally take the amount of time comparable to the age of the universe for this size group to reach the majority,” said SCNARC Director Boleslaw Szymanski, the Claire and Roland Schmitt Distinguished Professor at Rensselaer. “Once that number grows above 10 percent, the idea spreads like flame.”

This has implications for all kinds of things, from understanding how religious and political beliefs spread, to why certain fashion trends catch on. And it certainly sheds new light on the seemingly intractable debt ceiling debate, and how a committed minority can drive the entire conversation. The research actually validates the entrenched strategy of the handful of House Republicans threatening to sink John Boehner‘s budget proposal. Turns out if you’re in the minority, you have less of an incentive to compromise than the majority does. Because if you stick to your guns, and reach that crucial 10%, your ideas eventually win out. Just as the graph from SNARC below illustrates:

https://freakonomics.com/2011/07/minority-rules-why-10-percent-is-all-you-need

2011-08-05

It’s majority rule — even if only 10% believe it

To change the beliefs of an entire community, only 10 percent of the population needs to become convinced of a new or different opinion, suggests a new study. At that tipping point, the idea can spread through social networks and alter behaviors on a large scale.

The research is still in its early stages, and it’s uncertain if the results will apply to all kinds of beliefs, particularly in tense political situations.

But the findings do provide insight into how opinions spread through communities. The model may also help experts more effectively quell misconceptions and influence the choices people make about public health behaviors and related issues.

“This is really a starting point to understand how you can cause fast change in a population,” said Sameet Sreenivasan, a statistical physicist who specializes in network theory at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y.

“The real world has a lot more complexity, obviously,” he added. “But one of the things you can take away is that if you want to cause a fast change, there is an upper bound to how many people really need to commit.”

Previous modeling studies have treated opinions like infections, Sreenivasan said. They assumed that beliefs would spread like epidemics, but that’s not really an accurate depiction of the real world. He and his colleagues took a different approach.

The researchers started by creating three social network models each with groups of people with different links between them. In the first, everyone was connected to everyone. In another, everyone had the same average number of connections even though not every person was connected directly to everyone else. The third network included “opinion leaders,” who had more connections than others did.

At the beginning of the experiment, every node in each social network was set to share one opinion. The researchers also set the model to follow a specific set of rules. For example, “listener” nodes adopted the ideas of “speaker” nodes. And, once listeners adopted a minority opinion, they became inflexible and unshakable. They wouldn’t change their opinion again, but they could influence those they came in contact with.

When the researchers introduced a new, different opinion to a very tiny fraction of nodes, it took an exponentially long time for that belief to spread through the population. But when between 7 percent and 10 percent of the nodes became convinced of that second opinion, the researchers reported in the journal Physical Review E, there was a sharp drop in how long it took for the whole community to come to consensus. Rapidly, they all began to believe in that second opinion.

The exact proportion needed to reach the tipping point depended on the type of network involved. But all three types of network models produced the same conclusion, said Albert-Laszlo Barabasi, director of the Center for Complex Network Research at Northeastern University in Boston.

“The main message is that each opinion has a critical point,” Barabasi said. “If the fraction of the population is under the predicted threshold, the minority can prevail, but it will take astronomically long times to do so. However, once the number of people who are unshakable in their opinion reaches the critical threshold, the time it takes for the majority to accept their point of view becomes rather short.”

“It also shows that minorities can prevail in their opinion only if they strive to become less of a minority by turning a small fraction of the population to absorb their opinion,” he added, “becoming unshakable supporters of their point of view.”

The findings are not likely to apply to bipartisan debates about issues like debt ceilings and tax cuts. One reason, Sreenivasan said, is that those situations often involve unshakable opinions on both sides.

Instead, the study might be of use in public health campaigns, such as efforts to get people in Africa to start using bug nets to prevent disease.

Sreenivasan mentioned the fogging of insecticides as an anti-mosquito strategy in Arizona. People who wanted to end the spraying were running up against a long-held belief that smelling and seeing the toxic chemical was the only proof that something was being done about the bugs.

“In situations like that,” Sreenivasan said, “instead of trying to convince everyone, it might make the most sense to target the few people who are open-minded enough to hear out the evidence and make up their minds rationally.”

https://www.nbcnews.com/id/wbna44024703

2018-06-08

The 25% Revolution—How Big Does a Minority Have to Be to Reshape Society?

Social change—from evolving attitudes toward gender and marijuana to the rise of Donald Trump to the emergence of the Black Lives Matter and #MeToo movements—is a constant. It is also mysterious, or so it can seem. For example, “How exactly did we get here?” might be asked by anyone who lived through decades of fierce prohibition and now buys pot at one of the more than 2,000 licensed dispensaries across the U.S.

A new study about the power of committed minorities to shift conventional thinking offers some surprising possible answers. Published this week in Science, the paper describes an online experiment in which researchers sought to determine what percentage of total population a minority needs to reach the critical mass necessary to reverse a majority viewpoint. The tipping point, they found, is just 25 percent. At and slightly above that level, contrarians were able to “convert” anywhere from 72 to 100 percent of the population of their respective groups. Prior to the efforts of the minority, the population had been in 100 percent agreement about their original position.

“This is not about a small elite with disproportionate resources,” says Arnout van de Rijt, a sociologist at Utrecht University in the Netherlands who studies social networks and collective action, and was not involved in the study. “It’s not about the Koch brothers influencing American public opinion. Rather, this is about a minority trying to change the status quo, and succeeding by being unrelenting. By committing to a new behavior, they repeatedly expose others to that new behavior until they start to copy it.”

The experiment was designed and led by Damon Centola, associate professor in the Annenberg School of Communications at the University of Pennsylvania. It involved 194 people randomly assigned to 10 “independent online groups,” which varied in size from 20 to 30 people. In the first step group members were shown an image of a face and told to name it. They interacted with one another in rotating pairs until they all agreed on a name. In the second step Centola and his colleagues seeded each group with “a small number of confederates…who attempted to overturn the established convention (the agreed-on name) by advancing a novel alternative.”

For the second step, as Centola explains it, the researchers began with a 15 percent minority model and gradually increased it to 35 percent. Nothing changed at 15 percent, and the established norm remained in place all the way up to 24 percent.

The magic number, the tipping point, turned out to be 25 percent. Minority groups smaller than that converted, on average, just 6 percent of the population. Among other things, Centola says, that 25 percent figure refutes a century of economic theory. “The classic economic model—the main thing we are responding to with this study—basically says that once an equilibrium is established, in order to change it you need 51 percent. And what these results say is no, a small minority can be really effective, even when people resist the minority view.” The team’s computer modeling indicated a 25 percent minority would retain its power to reverse social convention for populations as large as 100,000.

But the proportion has to be just right: One of the groups in the study consisted of 20 members, with four contrarians. Another group had 20 members and five contrarians—and that one extra person made all the difference. “In the group with four, nothing happens,” Centola says, “and with five you get complete conversion to the alternative norm.” The five, neatly enough, represented 25 percent of the group population. “One of the most interesting empirical, practical insights from these results is that at 24 percent—just below the threshold—you don’t see very much effect,” adds Centola, whose first book, How Behavior Spreads: The Science of Complex Contagions, comes out this month. “If you are those people trying to create change, it can be really disheartening.” When a committed minority effort starts to falter there is what Centola calls “a convention to give up,” and people start to call it quits. And of course members have no way to know when their group is just short of critical mass. They can be very close and simply not realize it. “So I would say to Black Lives Matter, #MeToo and all of these social change movements that approaching that tipping point is slow going, and you can see backsliding. But once you get over it, you’ll see a really large-scale impact.”

Real-life factors that can work against committed minorities—even when they reach or exceed critical mass—include a lack of interaction with other members, as well as competing committed minorities and what’s called “active resistance”—which pretty well describes the way many people in 2018 respond to political ideas with which they disagree. But even with such obstacles, Centola says the tipping point predicted in his model remains well below 50 percent.

Certain settings lend themselves to the group dynamics Centola describes in his study, and that includes the workplace. “Businesses are really great for this kind of thing,” he says, “because people in firms spend most of their day trying to coordinate with other people, and they exhibit the conventions that other people exhibit because they want to show that they’re good workers and members of the firm. So you can see very strong effects of a minority group committed to changing the culture of the population.”

The other environment in which the 25 percent effect is particularly evident, Centola says, is online—where people have large numbers of interactions with lots of other people, many of them strangers. This raises some tricky questions: Can a bot stand in for a member of a committed minority? And can a committed minority be composed of bots and the real people the bots influence, so that bots are actually driving the change? According to Centola, “In a space where people can’t distinguish people from bots, yes. If you get a concerted, focused effort by a group of agents acting as a minority view, they can be really effective.”

Yale sociologist Emily Erikson, who also studies social networks but was not involved with the study, sees the new paper partly as a warning. “In some sense it’s saying extreme voices can quickly take over public discourse,” she says. “Perhaps if we’re aware of that fact, we can guard against it.”

2019-05-14

The ‘3.5% rule’: How a small minority can change the world

Nonviolent protests are twice as likely to succeed as armed conflicts – and those engaging a threshold of 3.5% of the population have never failed to bring about change.

In 1986, millions of Filipinos took to the streets of Manila in peaceful protest and prayer in the People Power movement. The Marcos regime folded on the fourth day.

In 2003, the people of Georgia ousted Eduard Shevardnadze through the bloodless Rose Revolution, in which protestors stormed the parliament building holding the flowers in their hands. While in 2019, the presidents of Sudan and Algeria both announced they would step aside after decades in office, thanks to peaceful campaigns of resistance.

In each case, civil resistance by ordinary members of the public trumped the political elite to achieve radical change.

There are, of course, many ethical reasons to use nonviolent strategies. But compelling research by Erica Chenoweth, a political scientist at Harvard University, confirms that civil disobedience is not only the moral choice; it is also the most powerful way of shaping world politics – by a long way.

Looking at hundreds of campaigns over the last century, Chenoweth found that nonviolent campaigns are twice as likely to achieve their goals as violent campaigns. And although the exact dynamics will depend on many factors, she has shown it takes around 3.5% of the population actively participating in the protests to ensure serious political change.

Chenoweth’s influence can be seen in the recent Extinction Rebellion protests, whose founders say they have been directly inspired by her findings. So just how did she come to these conclusions?

Needless to say, Chenoweth’s research builds on the philosophies of many influential figures throughout history. The African-American abolitionist Sojourner Truth, the suffrage campaigner Susan B Anthony, the Indian independence activist Mahatma Gandhi and the US civil rights campaigner Martin Luther King have all convincingly argued for the power of peaceful protest.

Yet Chenoweth admits that when she first began her research in the mid-2000s, she was initially rather cynical of the idea that nonviolent actions could be more powerful than armed conflict in most situations. As a PhD student at the University of Colorado, she had spent years studying the factors contributing to the rise of terrorism when she was asked to attend an academic workshop organised by the International Center of Nonviolent Conflict (ICNC), a non-profit organisation based in Washington DC. The workshop presented many compelling examples of peaceful protests bringing about lasting political change – including, for instance, the People Power protests in the Philippines.

But Chenoweth was surprised to find that no-one had comprehensively compared the success rates of nonviolent versus violent protests; perhaps the case studies were simply chosen through some kind of confirmation bias. “I was really motivated by some scepticism that nonviolent resistance could be an effective method for achieving major transformations in society,” she says

Working with Maria Stephan, a researcher at the ICNC, Chenoweth performed an extensive review of the literature on civil resistance and social movements from 1900 to 2006 – a data set then corroborated with other experts in the field. They primarily considered attempts to bring about regime change. A movement was considered a success if it fully achieved its goals both within a year of its peak engagement and as a direct result of its activities. A regime change resulting from foreign military intervention would not be considered a success, for instance. A campaign was considered violent, meanwhile, if it involved bombings, kidnappings, the destruction of infrastructure – or any other physical harm to people or property.

“We were trying to apply a pretty hard test to nonviolent resistance as a strategy,” Chenoweth says. (The criteria were so strict that India’s independence movement was not considered as evidence in favour of nonviolent protest in Chenoweth and Stephan’s analysis – since Britain’s dwindling military resources were considered to have been a deciding factor, even if the protests themselves were also a huge influence.)

By the end of this process, they had collected data from 323 violent and nonviolent campaigns. And their results – which were published in their book Why Civil Resistance Works: The Strategic Logic of Nonviolent Conflict – were striking.

Strength in numbers

Overall, nonviolent campaigns were twice as likely to succeed as violent campaigns: they led to political change 53% of the time compared to 26% for the violent protests.

This was partly the result of strength in numbers. Chenoweth argues that nonviolent campaigns are more likely to succeed because they can recruit many more participants from a much broader demographic, which can cause severe disruption that paralyses normal urban life and the functioning of society.

In fact, of the 25 largest campaigns that they studied, 20 were nonviolent, and 14 of these were outright successes. Overall, the nonviolent campaigns attracted around four times as many participants (200,000) as the average violent campaign (50,000).

The People Power campaign against the Marcos regime in the Philippines, for instance, attracted two million participants at its height, while the Brazilian uprising in 1984 and 1985 attracted one million, and the Velvet Revolution in Czechoslovakia in 1989 attracted 500,000 participants.

“Numbers really matter for building power in ways that can really pose a serious challenge or threat to entrenched authorities or occupations,” Chenoweth says – and nonviolent protest seems to be the best way to get that widespread support.

Once around 3.5% of the whole population has begun to participate actively, success appears to be inevitable.

<...>

“There weren’t any campaigns that had failed after they had achieved 3.5% participation during a peak event,” says Chenoweth – a phenomenon she has called the “3.5% rule”. Besides the People Power movement, that included the Singing Revolution in Estonia in the late 1980s and the Rose Revolution in Georgia in the early 2003.

Chenoweth admits that she was initially surprised by her results. But she now cites many reasons that nonviolent protests can garner such high levels of support. Perhaps most obviously, violent protests necessarily exclude people who abhor and fear bloodshed, whereas peaceful protesters maintain the moral high ground.

Chenoweth points out that nonviolent protests also have fewer physical barriers to participation. You do not need to be fit and healthy to engage in a strike, whereas violent campaigns tend to lean on the support of physically fit young men. And while many forms of nonviolent protests also carry serious risks – just think of China’s response in Tiananmen Square in 1989 – Chenoweth argues that nonviolent campaigns are generally easier to discuss openly, which means that news of their occurrence can reach a wider audience. Violent movements, on the other hand, require a supply of weapons, and tend to rely on more secretive underground operations that might struggle to reach the general population.

By engaging broad support across the population, nonviolent campaigns are also more likely to win support among the police and the military – the very groups that the government should be leaning on to bring about order.

During a peaceful street protest of millions of people, the members of the security forces may also be more likely to fear that their family members or friends are in the crowd – meaning that they fail to crack down on the movement. “Or when they’re looking at the [sheer] numbers of people involved, they may just come to the conclusion the ship has sailed, and they don’t want to go down with the ship,” Chenoweth says.

In terms of the specific strategies that are used, general strikes “are probably one of the most powerful, if not the most powerful, single method of nonviolent resistance”, Chenoweth says. But they do come at a personal cost, whereas other forms of protest can be completely anonymous. She points to the consumer boycotts in apartheid-era South Africa, in which many black citizens refused to buy products from companies with white owners. The result was an economic crisis among the country’s white elite that contributed to the end of segregation in the early 1990s.

“There are more options for engaging and nonviolent resistance that don’t place people in as much physical danger, particularly as the numbers grow, compared to armed activity,” Chenoweth says. “And the techniques of nonviolent resistance are often more visible, so that it’s easier for people to find out how to participate directly, and how to coordinate their activities for maximum disruption.”

A magic number?

These are very general patterns, of course, and despite being twice as successful as the violent conflicts, peaceful resistance still failed 47% of the time. As Chenoweth and Stephan pointed out in their book, that’s sometimes because they never really gained enough support or momentum to “erode the power base of the adversary and maintain resilience in the face of repression”. But some relatively large nonviolent protests also failed, such as the protests against the communist party in East Germany in the 1950s, which attracted 400,000 members (around 2% of the population) at their peak, but still failed to bring about change.

In Chenoweth’s data set, it was only once the nonviolent protests had achieved that 3.5% threshold of active engagement that success seemed to be guaranteed – and raising even that level of support is no mean feat. In the UK it would amount to 2.3 million people actively engaging in a movement (roughly twice the size of Birmingham, the UK’s second largest city); in the US, it would involve 11 million citizens – more than the total population of New York City.

The fact remains, however, that nonviolent campaigns are the only reliable way of maintaining that kind of engagement.

Chenoweth and Stephan’s initial study was first published in 2011 and their findings have attracted a lot of attention since. “It’s hard to overstate how influential they have been to this body of research,” says Matthew Chandler, who researches civil resistance at the University of Notre Dame in Indiana.

Isabel Bramsen, who studies international conflict at the University of Copenhagen agrees that Chenoweth and Stephan’s results are compelling. “It’s [now] an established truth within the field that the nonviolent approaches are much more likely to succeed than violent ones,” she says.

Regarding the “3.5% rule”, she points out that while 3.5% is a small minority, such a level of active participation probably means many more people tacitly agree with the cause.

These researchers are now looking to further untangle the factors that may lead to a movement’s success or failure. Bramsen and Chandler, for instance, both emphasise the importance of unity among demonstrators.

As an example, Bramsen points to the failed uprising in Bahrain in 2011. The campaign initially engaged many protestors, but quickly split into competing factions. The resulting loss of cohesion, Bramsen thinks, ultimately prevented the movement from gaining enough momentum to bring about change.

Chenoweth’s interest has recently focused on protests closer to home – like the Black Lives Matter movement and the Women’s March in 2017. She is also interested in Extinction Rebellion, recently popularised by the involvement of the Swedish activist Greta Thunberg. “They are up against a lot of inertia,” she says. “But I think that they have an incredibly thoughtful and strategic core. And they seem to have all the right instincts about how to develop and teach through a nonviolent resistance campaigns.”

Ultimately, she would like our history books to pay greater attention to nonviolent campaigns rather than concentrating so heavily on warfare. “So many of the histories that we tell one another focus on violence – and even if it is a total disaster, we still find a way to find victories within it,” she says. Yet we tend to ignore the success of peaceful protest, she says.

“Ordinary people, all the time, are engaging in pretty heroic activities that are actually changing the way the world – and those deserve some notice and celebration as well.”

https://www.bbc.com/future/article/20190513-it-only-takes-35-of-people-to-change-the-world